UK Soils Awareness Week

#uksaw

Soils Lexicon

Use this handy guide to learn some of the critical terminology you need at your fingertips to understand and explain soil.

Jump to a Lexicon entry:

What is soil?

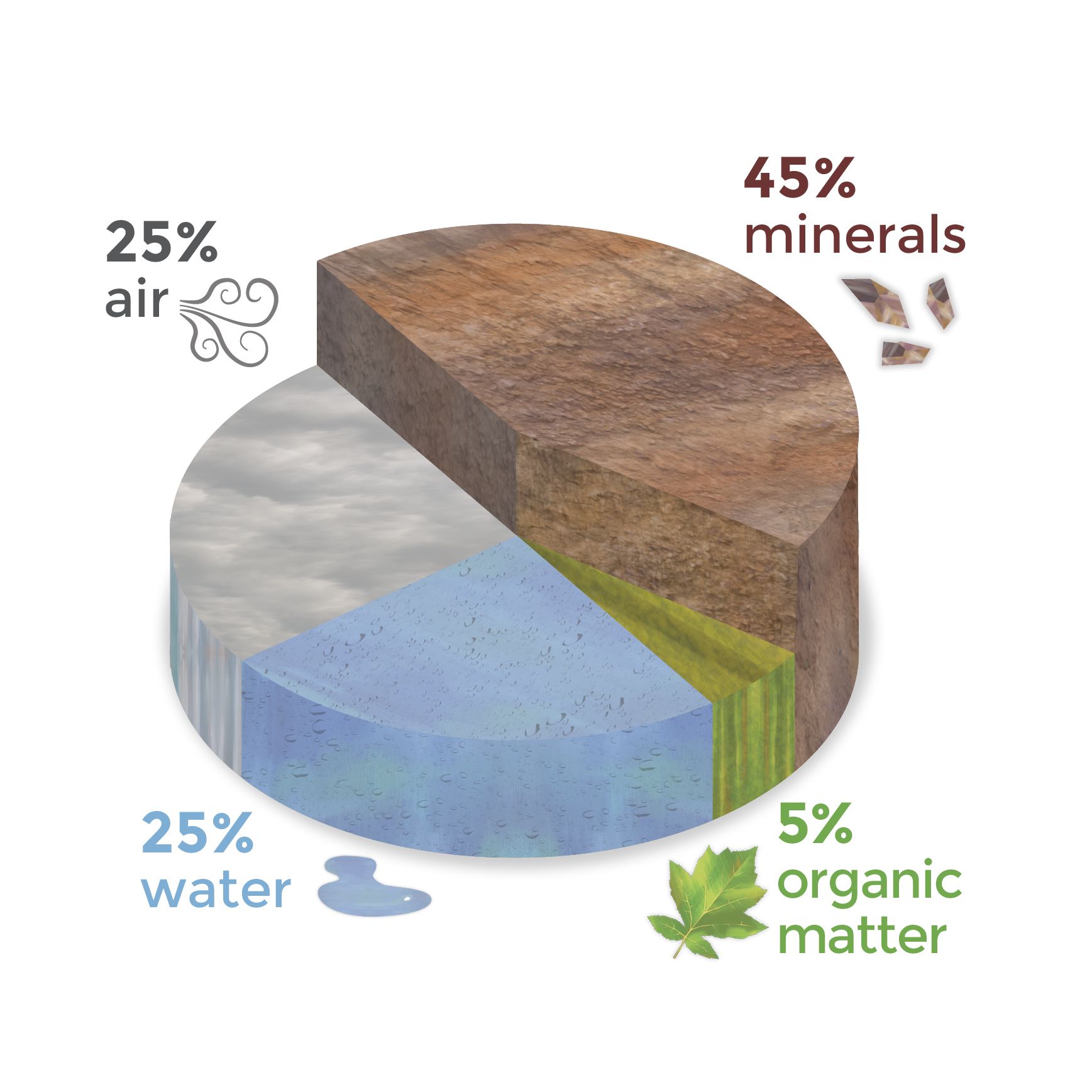

Soil is the loose upper layer of the Earth consisting of air, water, organic matter and minerals. It is also a vital source of food and medicine, home to a vast reservoir of biodiversity and an important store of carbon – so vital for all life on earth!

Soils can be understood in lots of different ways:

- As the loose upper layer of the Earth made up of air, water, organic matter and minerals

- As an ecosystem providing a home for millions of organisms to interact

- As the means of structural support for plants – and the source of water and nutrients they need to grow

- As the black or dark brown material that gets on your shoes and your carpets!

All of these are true – but soil is so much more than that! Soil is a dynamic and diverse ecosystem that lies at the interface between earth, air, water, and life.

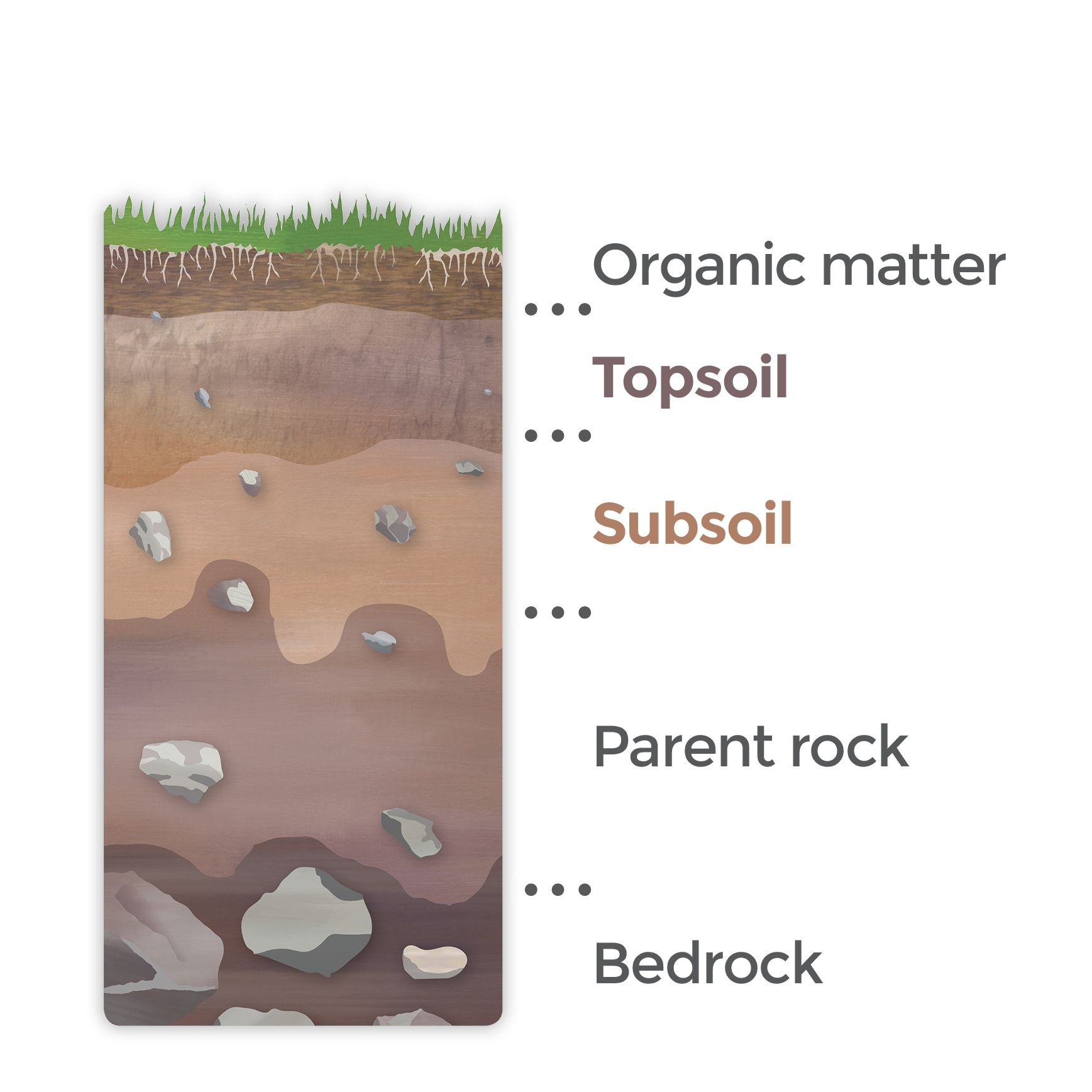

Topsoil and subsoil

Soil is made up of two layers – both crucial for plant growth. Topsoil (0 – 15 cm) has the highest amount of microorganisms and organic matter, while the Subsoil beneath is denser and less fertile but critical for drainage and nutrient supply.

Topsoil is the surface of the soil, typically 0 – 15 cm deep. It has the highest amount of microorganisms and organic matter and is where most of the biological activity takes place.

Subsoil is to be found below the topsoil. It has less organic content but more minerals and is more compact because it holds less air. Although subsoil is less fertile than topsoil, it is nevertheless crucial for plant growth because of its impact on water absorption, mineral availability and drainage.

The higher concentration of organic matter makes topsoil much darker than subsoil. The consistency is also different. Topsoil is usually very porous and has a light feel to it, whereas subsoil is more tightly packed together.

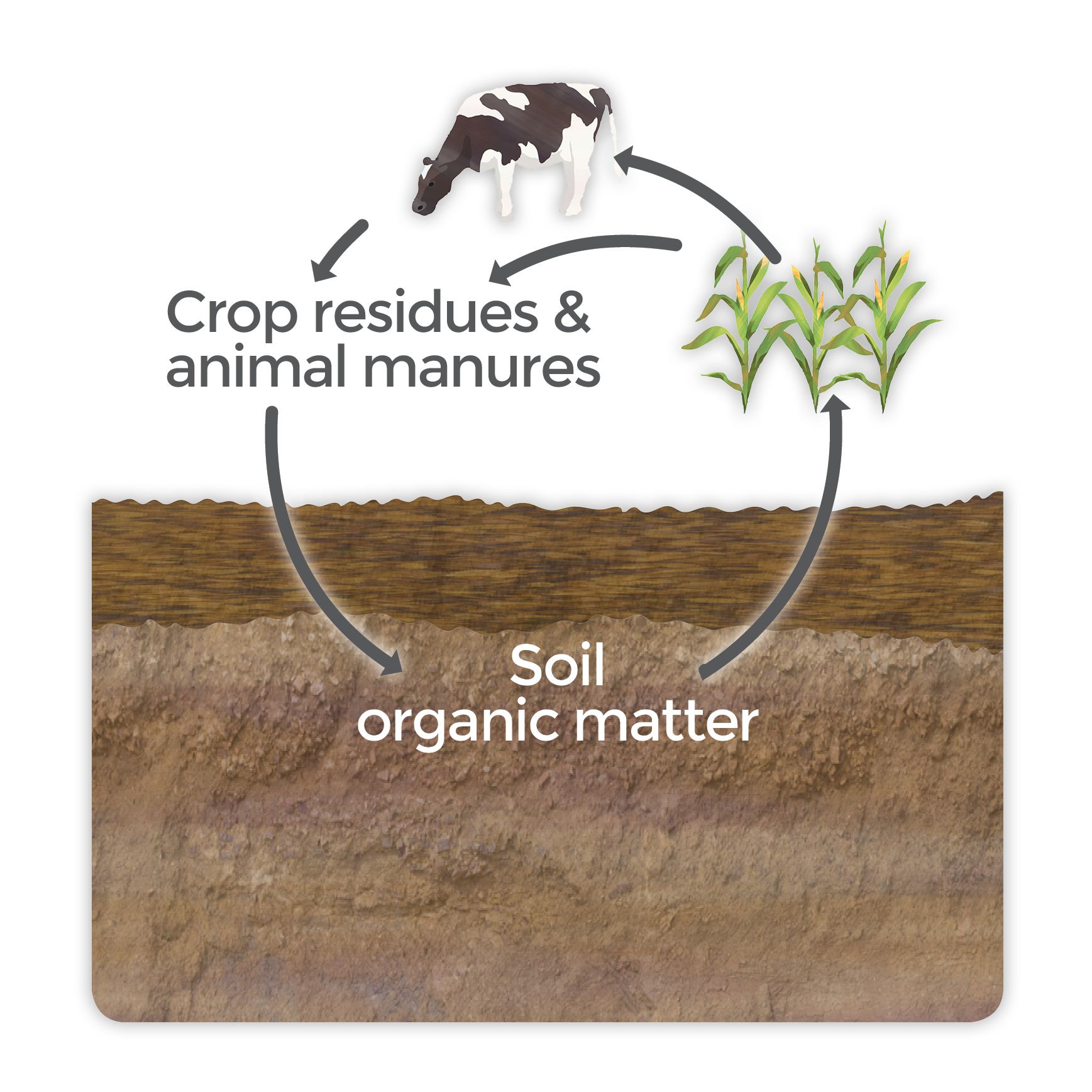

Soil Organic Matter

Soil Organic Matter consists of plant residues, living organisms and decomposing matter and is an important indicator of a soil’s quality. UK soils store over 10 billion tonnes of carbon in the form of organic matter.

Soil Organic Matter (SOM) is the most ‘active’ part of the topsoil, consisting of plant residues, living organisms and decomposing matter. The percentage of SOM in a soil is an important indicator of a soil’s quality for farming. It significantly improves the soil’s capacity to store and supply essential nutrients and improves soil structure which helps to control soil erosion. Since more than half (58%) of SOM is made up of carbon, increasing the amount of SOM in our soil is one of the solutions for mitigating climate change.

UK soils store over 10 billion tonnes of carbon in the form of organic matter.

Weathering

Weathering is the process whereby rocks are broken down by physical, chemical and biological activity by plants and microbes and climate processes to a point where they can be formed into soil. This can happen rapidly over a decade or slowly over millions of years.

The amount of minerals varies for different soil types and by depth. These minerals come from the breakdown of rocks by a mix of physical, chemical and biological activity by plants and microbes and climate processes. This process of the breakdown of rocks is called weathering. Weathering may proceed rapidly over a decade or slowly over millions of years.

It is from the rocks and sediments broken down by weathering that soils inherit many of their particular properties – in particular their texture. Since there is a very wide variety of rocks in the world, some acidic, some alkaline, some coarse-textured like sands, and some fine-textured and clayey, there is an equally diverse range of soils.

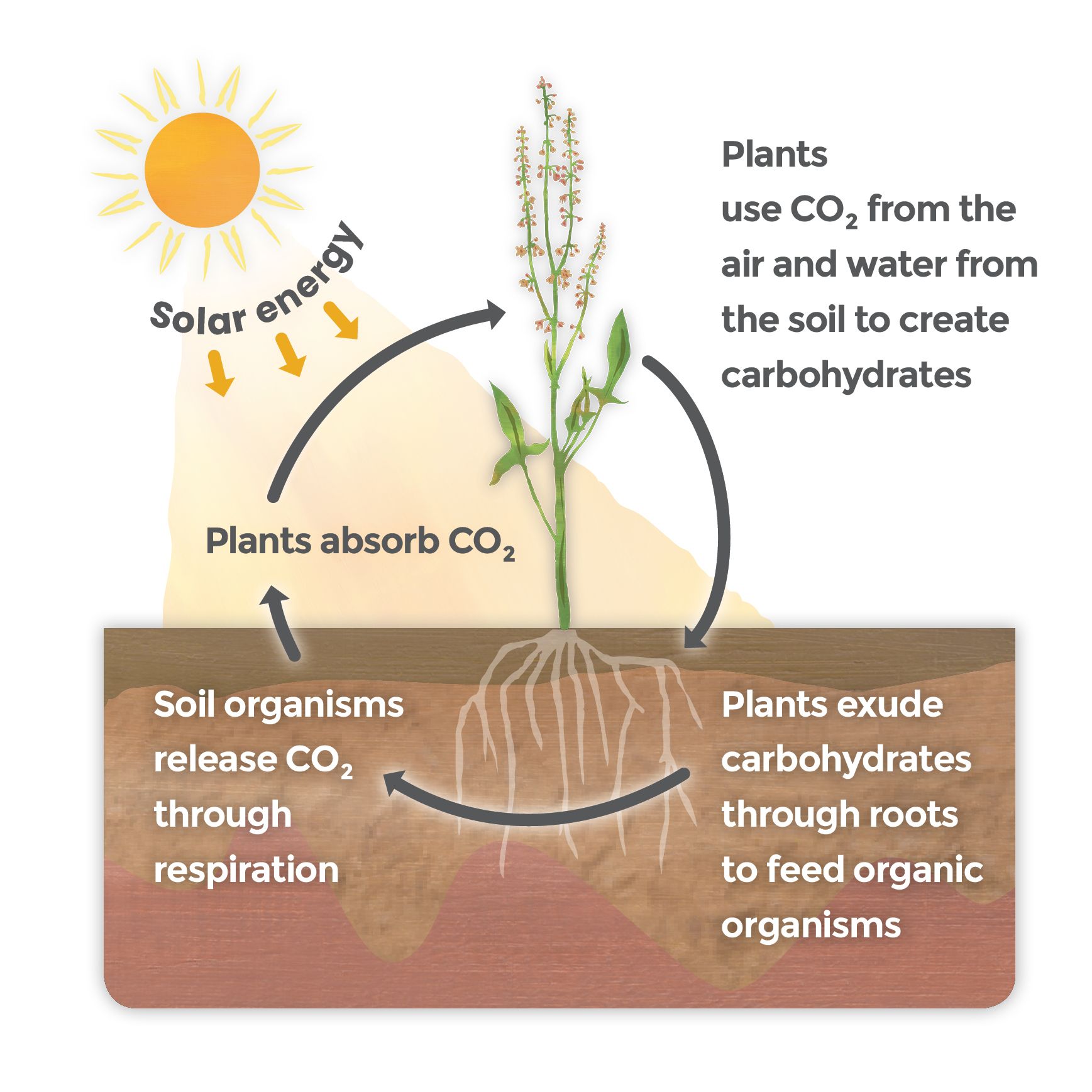

Soil carbon sequestration

Soil carbon sequestration happens when plants capture and store, or “sequester,” atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) in the soil. Some farming practices can increase this rate of storage, while others cause carbon to be released back into the atmosphere.

During carbon sequestration by soils, carbon is taken out of the atmosphere by photosynthesis and then incorporated into the soil via plant roots by microorganisms. That carbon cannot be said to have been ‘sequestered’ until it has been stabilised in the soil by being adsorbed onto soil minerals.

Some farming practices, like the addition of organic matter and planting cover crops, can increase this rate of storage, while others – leaving the earth bare and continued disturbance – release this carbon back into the atmosphere. Increasing soil organic carbon is important for climate change mitigation but also for soil health and fertility.

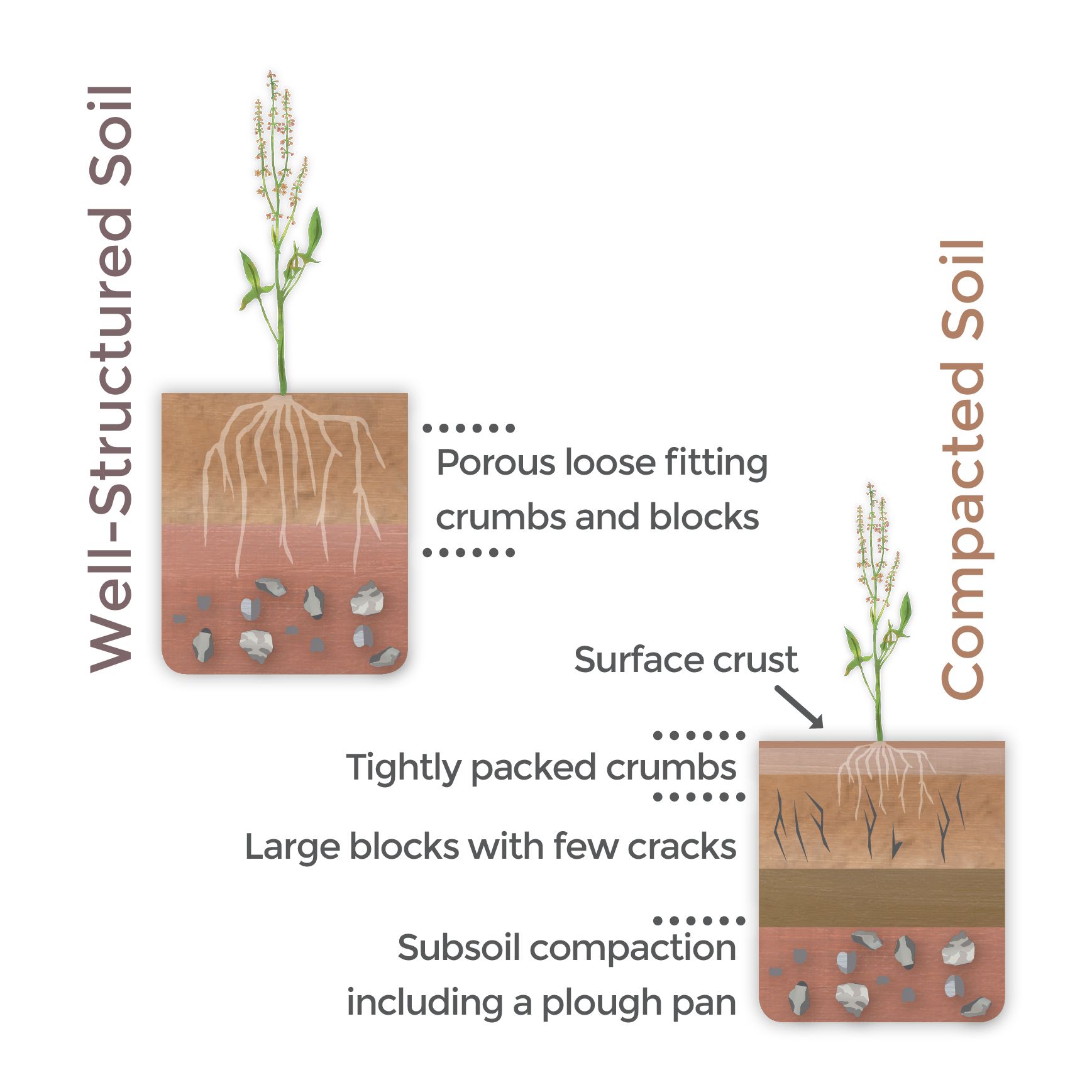

Soil compaction

Soil compaction occurs when the air pockets and channels in soil are compressed, reducing the space between the pores and preventing the filtration and movement of air and water. It is usually caused by farming in wet conditions.

The principal cause of compaction in the UK is farming in wet conditions – either by heavy machinery or high density of animals in a small area. In our uplands, animal numbers and the heavier weight of new animal breeds can cause widespread compaction on sensitive soils.

Filtration and the movement of air and water through soil are critical processes supporting life in soil.

Plant roots can’t enter compacted soil, preventing them from reaching the water and nutrients they need and making them less resilient to drought. Water also can’t penetrate compacted soil which increases the likelihood of flooding. Compacted soil is also less able to sequester carbon.

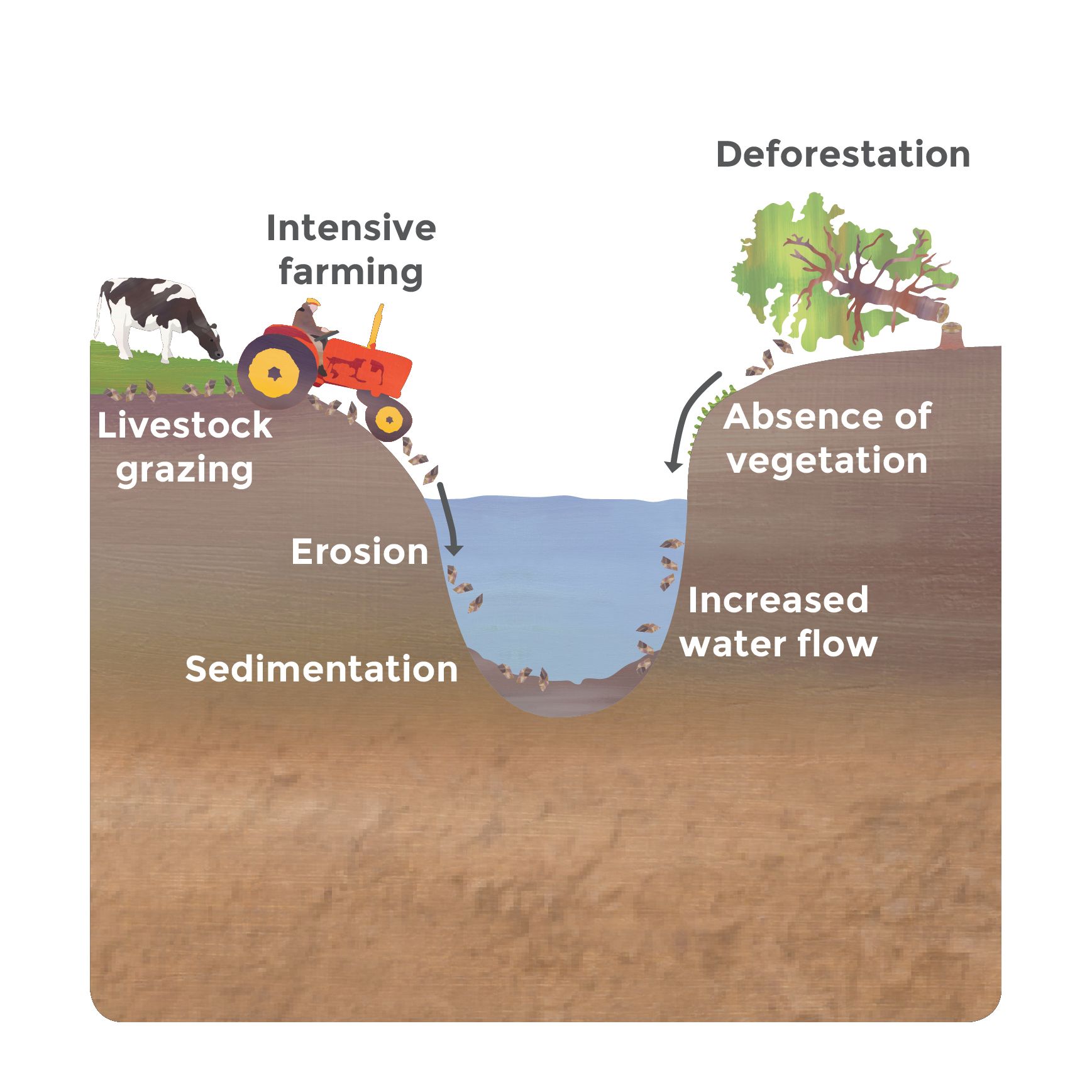

Soil erosion

Soil erosion is a natural process whereby topsoil is carried away by the wind and/or water, however it is made worse by human activities including intensive farming practices and deforestation. Over 2 million hectares of soil are at risk of erosion in England and Wales.

Soil eroded from the land, containing pesticides and fertilisers applied to fields, washes into streams and waterways causing sedimentation and pollution which in turn destroys aquatic life.

A growing problem is soil erosion along stream and river banks. Whilst this is a natural process, it is being accelerated by a lack of vegetation, faster flow and poaching by animals - removing a valuable resource for wildlife on land and impacting on our freshwater and coastal systems.

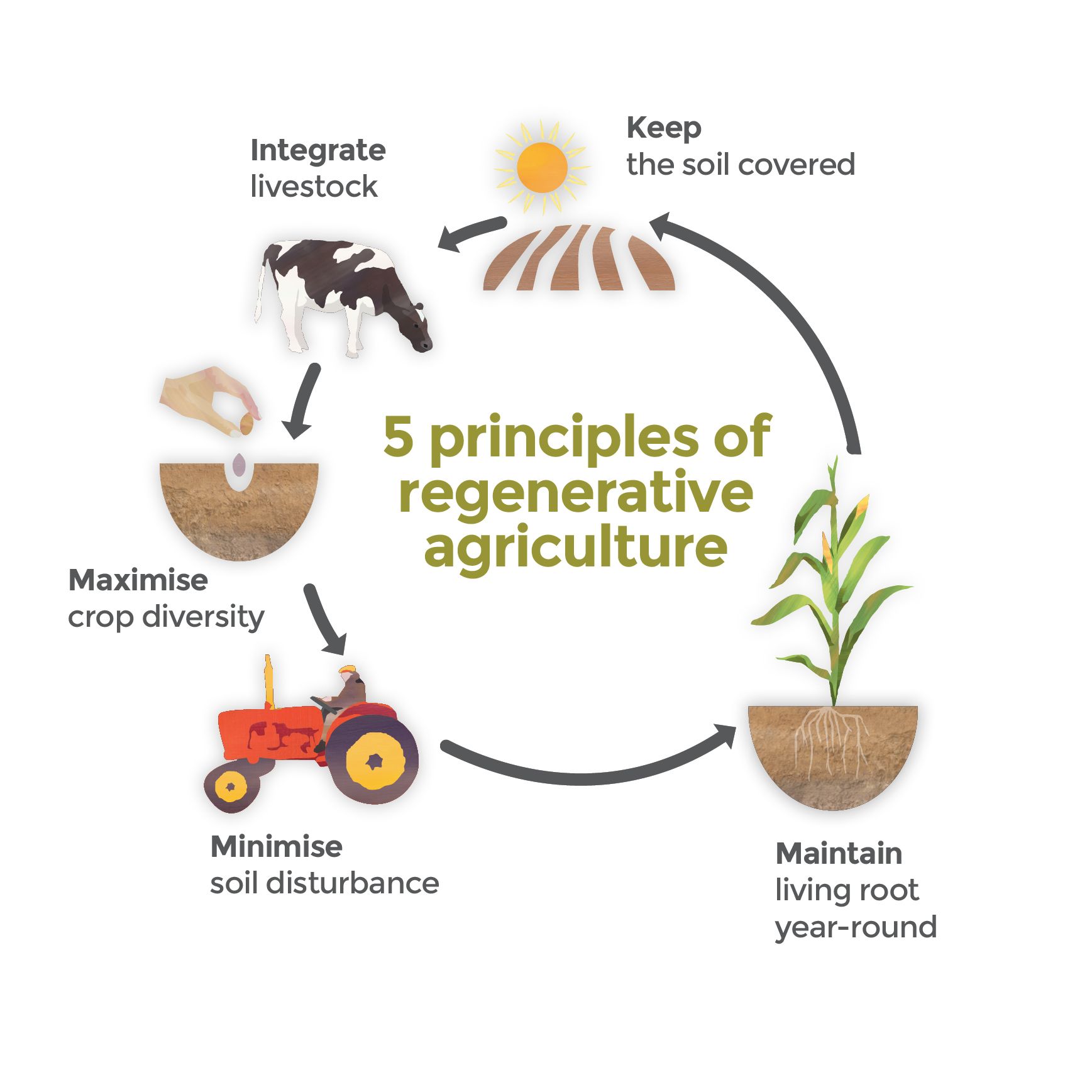

Regenerative farming

Regenerative Farming is a relatively new approach to farming that seeks to regenerate the land, soil and water, as well as enhance the wider environment and improve the nutrient density of food produced. It is loosely based on 5 core principles.

There is no fixed definition of regenerative – allowing farmers some flexibility about how to apply it to their land, but it is loosely based on five common principles:

- Keep the soil covered

- Maintain living roots year-round

- Minimise soil disturbance

- Maximise crop diversity

- Integrate livestock.

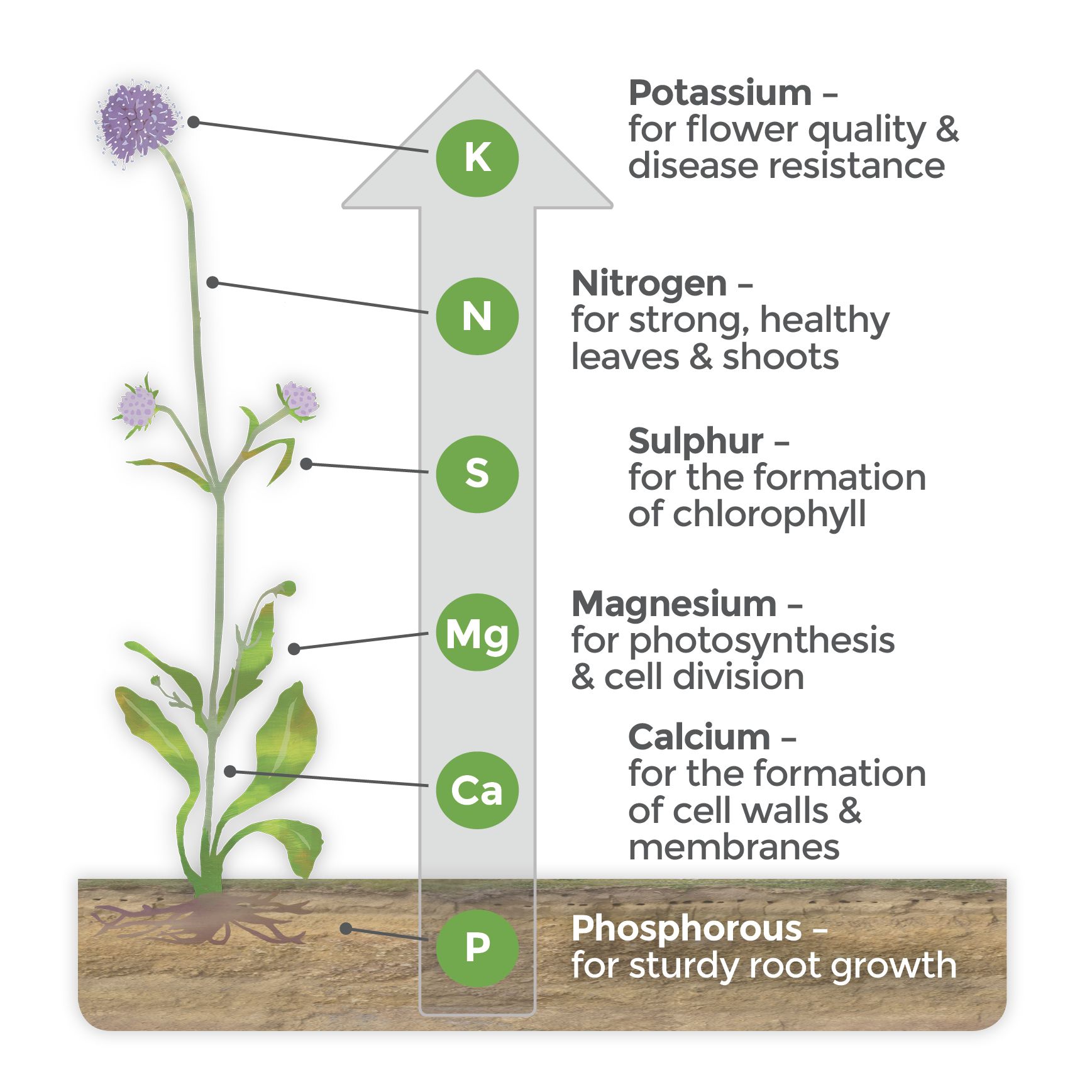

Nutrients

Soil is a major source of nutrients needed by plants for growth, development, reproduction and fighting off disease. Though their exact needs vary, most plants need three main nutrients to survive: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorous (P), and Potassium (K).

Nitrogen (N) is needed for strong, healthy stems, leaves and shoots.

Phosphorus (P) promotes sturdy root growth.

Potassium (K) improves flower quality and helps with disease resistance.

Other important nutrients are calcium, magnesium and sulphur. These nutrients come from a mix of decomposing organic matter, minerals in the soil and the atmosphere.

There are interesting links between pollution and nutrient availability. For example, increased nitrogen from the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels and farm animal waste products is beneficial for agricultural land, but is bad news for many of our native plants which are out-competed by tall grasses and weeds – which are supercharged by this surplus nitrogen.

Biodiversity

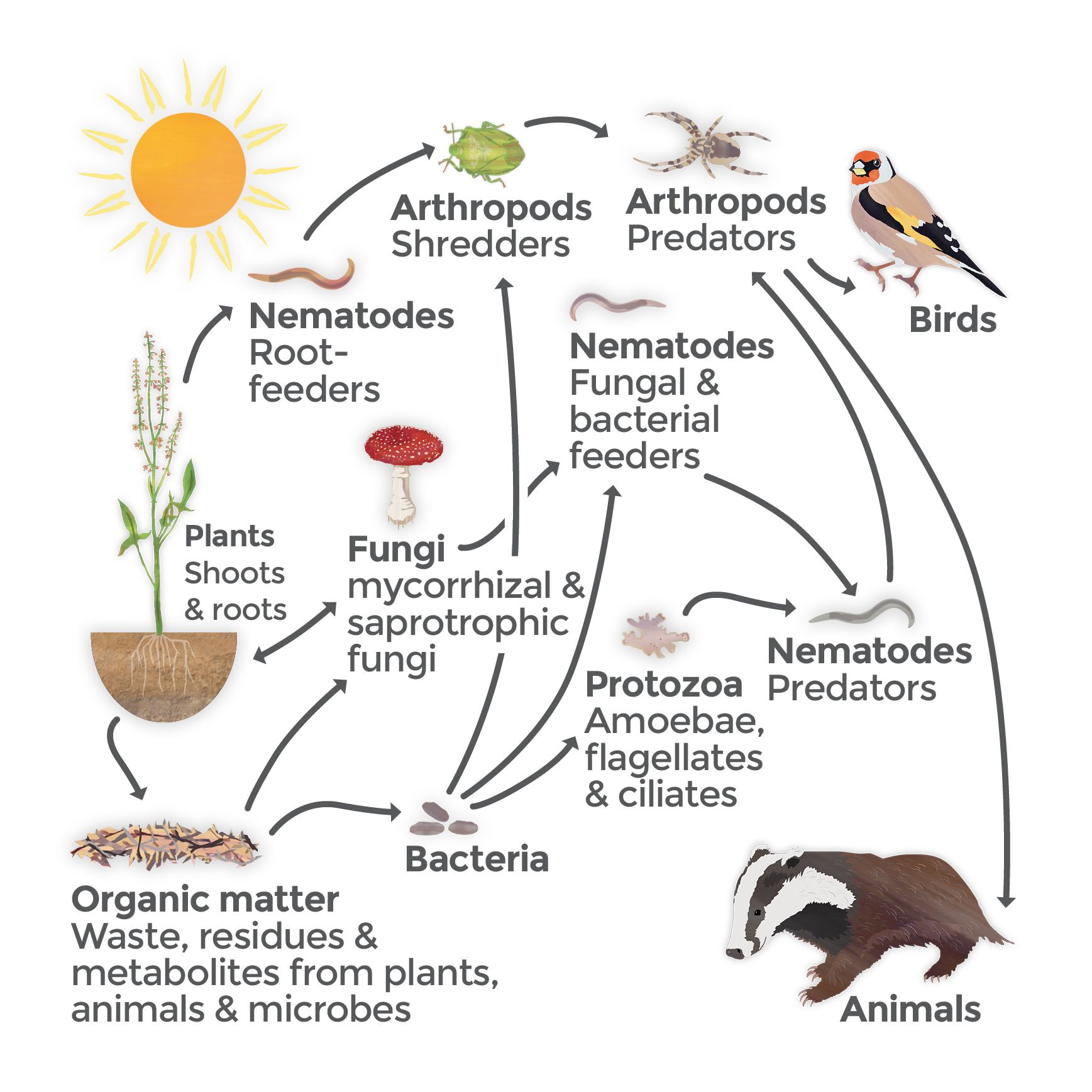

One teaspoon of soil contains more living organisms than there are people in the world. These micro-organisms provide a range of essential ecosystem services nutrient cycling, regulating soil organic matter, modifying the soil’s physical structure – so full of life and vital for all lie on earth!

Most soil dwelling organisms are not visible to the naked eye. They include microorganisms (bacteria, fungi), meso-fauna (acari and springtails), as well as the more familiar macro-fauna such as earthworms and termites. And of course plant roots live in the soil and provide the main supply of energy and nutrients to soil organisms through decaying roots and the release of fluids or exudates.

These diverse organisms contribute a wide range of essential ecosystem services. This includes nutrient cycling, regulating soil organic matter, modifying the soil’s physical structure and influencing the rates of nutrient acquisition by the vegetation and enhancing plant health. These organisms also are an important potential resource for future products such as antibiotics. Most commonly used antibiotics come from organisms which live in the soil.

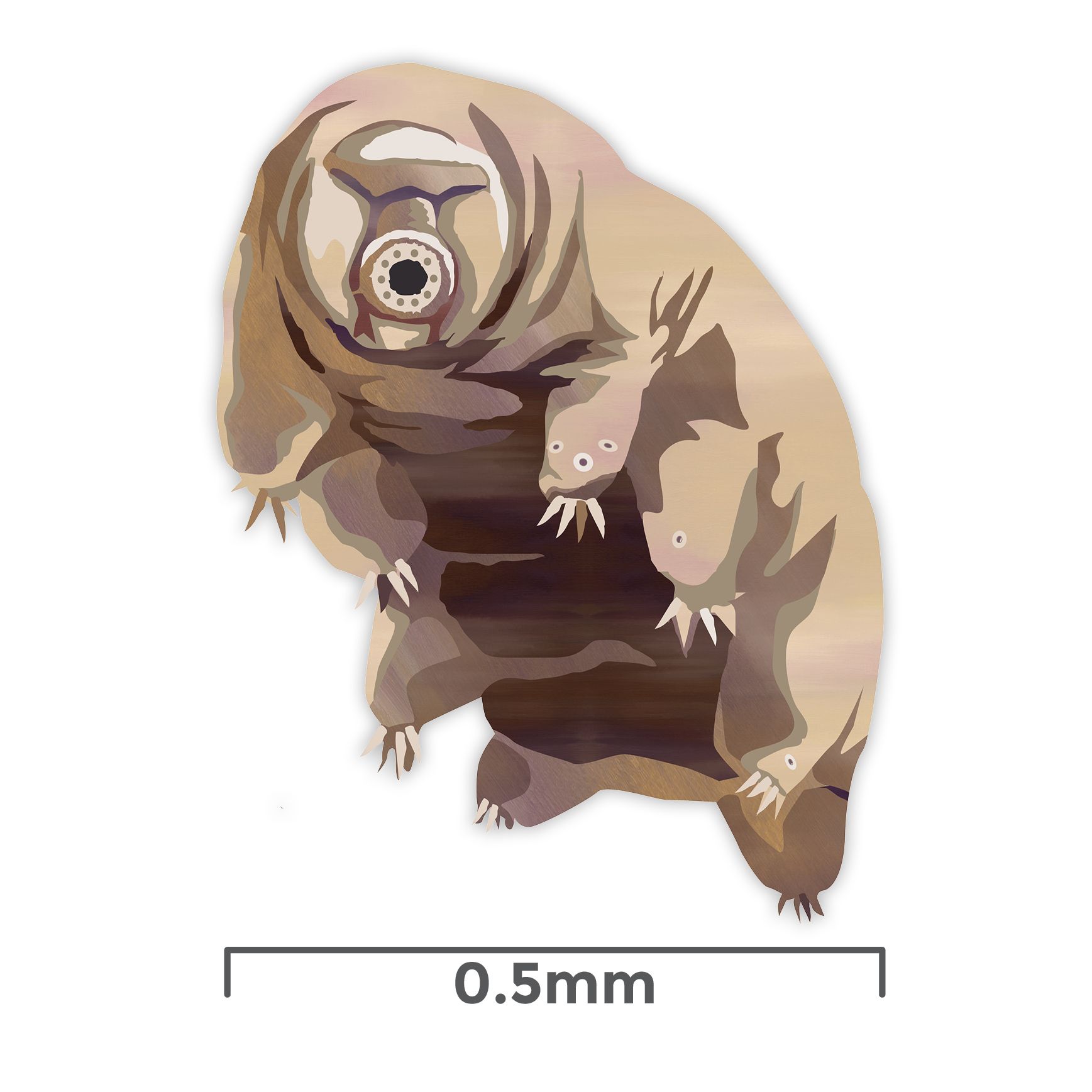

Tardigrades

Tardigrades are an example of a soil animal. They are also known as ‘water bears’ and are extremely hardy – in fact they were the first multicellular animal to survive exposure to outer space!

Measuring about 1mm in size, Tardigrades, which are also known as ‘water bears’ or ‘moss piglets’, are extremely hardy. Scientists say that tardigrades may have been among the first animals to leave the ocean and settle on dry land, and the first multicellular animal to survive exposure to outer space, although they prefer soil.

Other UK Soils Awareness Week content